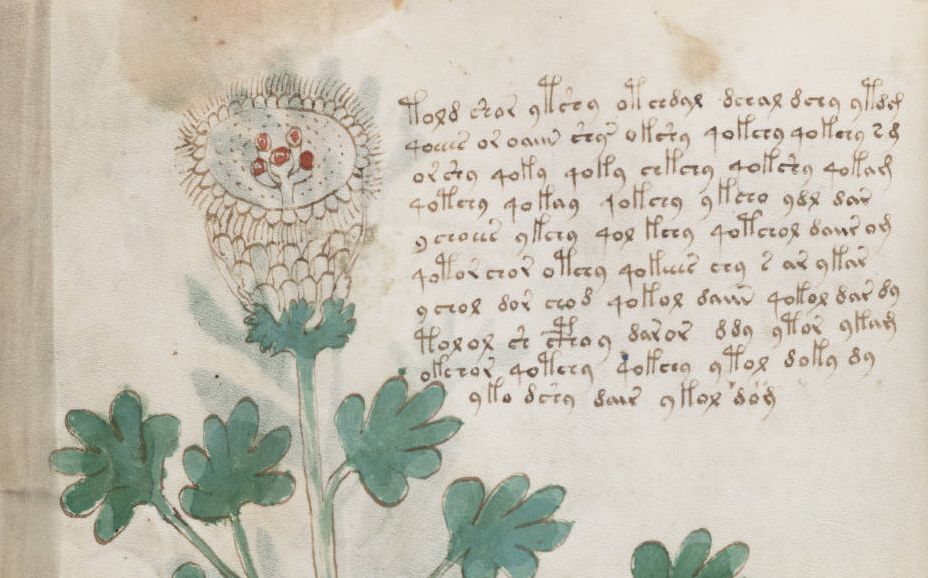

Do we miss them?

These letters were left out of the English alphabet, and here's why

Published on December 1, 2025

Credit: Ksenia Makagonova

Credit: Ksenia Makagonova

Some letters and symbols were once part of the English alphabet or its ancestors. But time and lack of use eventually made them be dropped, replaced, or forgotten. Most of them come from Old English, Middle English, Latin, or early printing traditions, and their stories are full of phonetic shifts, shortcuts, and the drive toward standardization. Let’s look at them!

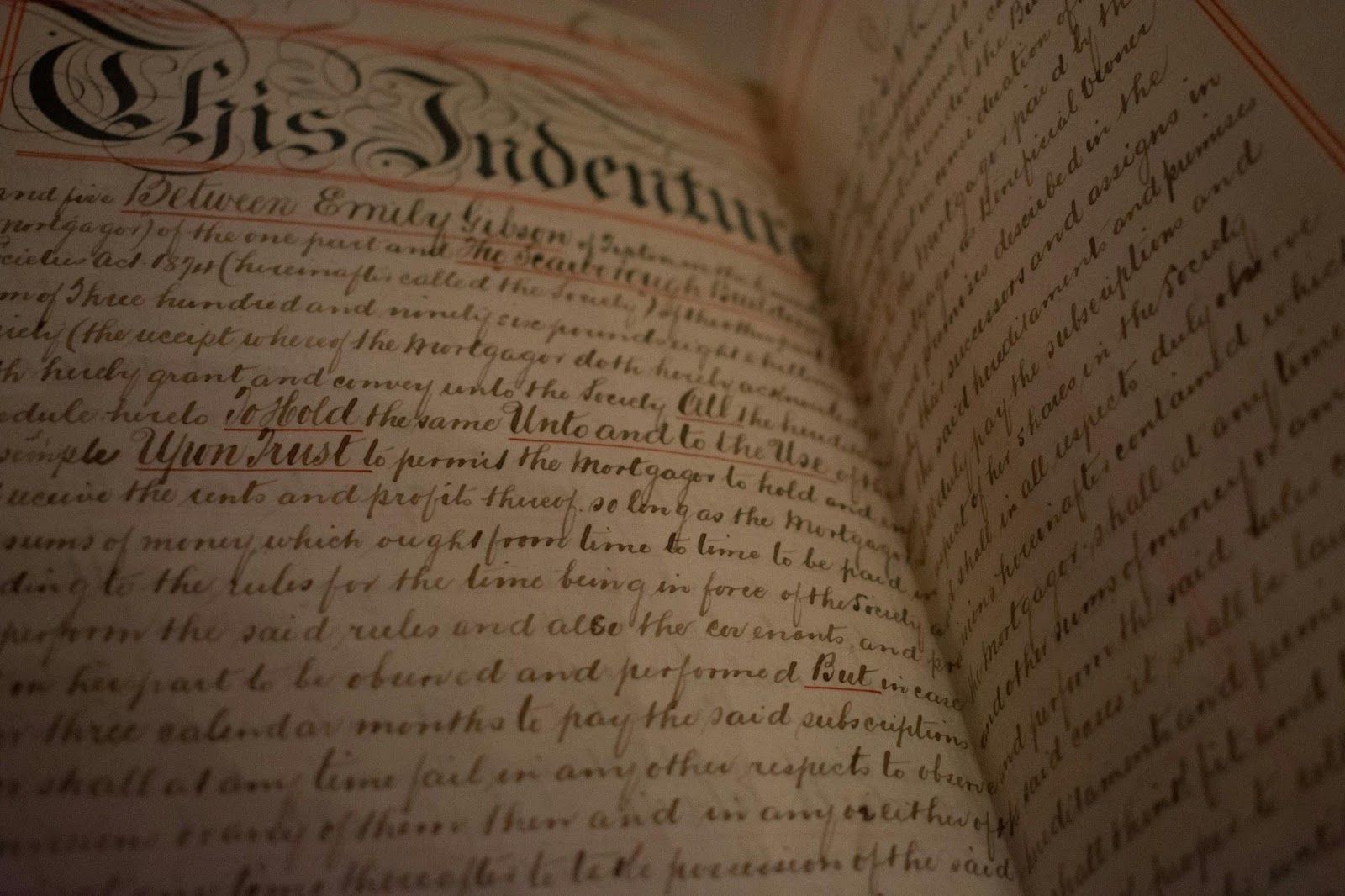

Thorn (Þ, þ)

Credit: Andrey Grinkevich

Credit: Andrey Grinkevich

Thorn was used to represent the "th" sound in words like thin or this. It visually resembled a modern P, which often causes confusion when seen in old manuscripts.

Common in Old English, it eventually got phased out during the Middle English period, replaced by the two-letter combination th. Thorn survives today in modern Icelandic, though!

Eth (Ð, ð)

Credit: James Barnett

Credit: James Barnett

Eth was another letter used to represent the "th" sound, particularly the voiced version. It looked a bit like a crossed D and appeared alongside thorn in Old English texts.

Over time, English speakers settled on using "th" for both the voiced and voiceless sounds, and eth gradually fell out of use. Like thorn, eth still exists in modern Icelandic.

Wynn (Ƿ, ƿ)

Credit: MART PRODUCTION

Credit: MART PRODUCTION

Wynn was used to represent the "w" sound in Old English—a sound that Latin lacked a letter for. It resembled a capital "P," though it had no connection to that sound.

Instead of writing two "u"s (as in "uu"), scribes used wynn. Over time, however, "uu" evolved into the modern "w," and wynn was phased out during the Middle English period.

Yogh (Ȝ, ȝ)

Credit: Josué AS

Credit: Josué AS

Yogh had a rather confusing role. It could represent several sounds: a throaty "gh" like in "night," a "y" as in "yes," or even a soft "g" like in "genre," depending on context and region. It looked like the number 3 and was used heavily in Middle English.

As spelling and pronunciation evolved, these sounds were either lost or spelled differently (gh, y, j, or g).

Ash (Æ, æ)

Credit: Bruno Martins

Credit: Bruno Martins

Ash is a fusion of "a" and "e," borrowed from Latin and used in Old English words like æthel (noble). It represented a distinct vowel sound, somewhere between "a" and "e," like the short "a" in cat.

In early English texts, it was treated as a letter in its own right. Over time, as English spelling standardized, ash was replaced by "a" or "e" depending on pronunciation.

Ethel (Œ, œ)

Credit: Natalia Y.

Credit: Natalia Y.

Think of Ethel as a relative of ash. This ligature combines "o" and "e" and shows up in Latin borrowings like fœtus, œuvre, and œconomy. As spelling was standardized, it got the axe in favor of plain old "oe" or even just "e."

You’ll still spot it in French and in stylized English writing.

Tironian et (⁊)

Credit: Jo Coenen - Studio Dries 2.6

Credit: Jo Coenen - Studio Dries 2.6

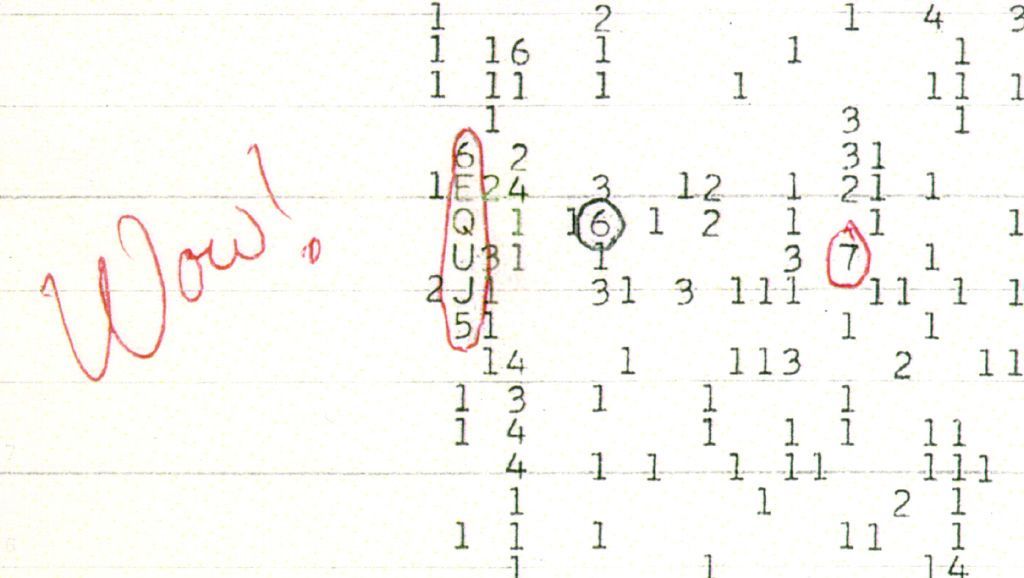

This curious mark, which resembles a 7, means "and." Created by Cicero’s secretary Tiro in ancient Rome, it became a popular shorthand used by monks and scribes throughout the medieval world, including in Old English.

In Ireland, it persisted longer than almost anywhere else, until the more elegant ampersand (&) eventually took its place.

Ampersand (&)

Credit: Mark Wieder

Credit: Mark Wieder

Well, we know this one! But as a symbol, not as a letter from the alphabet. Once upon a time, schoolchildren recited it after "Z": X, Y, Z, and "per se and," which eventually morphed into the word "ampersand."

The symbol itself is a ligature of the Latin word et, meaning "and."

Insular G (ᵹ)

Credit: Mark Rasmuson

Credit: Mark Rasmuson

This one looked like a medieval mashup of a "g" and a "z," and was mostly found in Irish and Old English manuscripts.

It served the same purpose as today’s "g." It stuck around until the Carolingian script took over, giving us the more familiar "g" we know today.

Long S (ſ)

Credit: Ot van Lieshout

Credit: Ot van Lieshout

At first glance, the Long S (ſ) looks like a stretched-out "f" missing its crossbar, but it’s an "s" in disguise. This character was used at the start and middle of words (e.g., ſunshine, bleſſing), but never at the end.

The character was ubiquitous in English printing until the late 1700s, when it was gradually replaced by the modern "s."

Eng (Ŋ, ŋ)

Credit: Aaron Burden

Credit: Aaron Burden

The letter itself sounded like the "ng" at the end of "fang" or "sing."

The letter resembles an "n" with a tail and remains in use today in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) and in languages such as Sami and Māori. However, English spelling never officially adopted it.